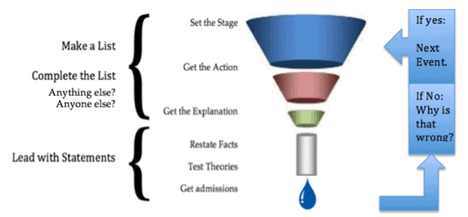

Abstract: The structure of a deposition is often portrayed as a funnel, with the top of the funnel representing open-ended questions used for gathering information. The narrow bottom of the funnel represents the effort to lead the witness into making admissions that help the attorney taking the deposition. This article describes how to refine that approach by using story-telling techniques and rethinking what it means to lead a witness.

An effective story allows a person to visualize not just the action but also the setting. Take, for example, Charles Dickens’ opening paragraph in Bleak House:

London. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

This paragraph says nothing about the plot of the novel but conveys a picture of crowded, muddy London streets on a dreary November day. Those types of vivid descriptions of place are as critical to an attorney’s story as they are for Dickens. They precede a description of the plot, which in turn precedes the reader’s ability to interpret events in the story to understand the purpose or moral of the story.

Most people now take in the setting visually in movies, TV and videos. The idea of the setting as a critical element of story telling is often overlooked because setting is taken for granted in visual presentation of a story.

But trials are mostly presented through words. As a result, the setting must be consciously presented in the questions and answers at trial. To do that, information on setting must be obtained in depositions. Otherwise the story is garbled and critical information omitted or misunderstood.

As attorneys, we always want to know what happened and what motivated each participant in the events leading to the court case. But in jumping to the plot and the moral of the story we risk leaving out story elements that provide context and aid comprehension for the trier of fact.

In order to comprehensively and systematically gather information and ensure thorough understanding of events, an attorney must take specific steps in a particular order when gathering information at the top of the funnel:

- Stage setting

- Action

- Explanation

The term “stage setting” is based on the idea that if you go to a play you get important information before you see the action. The playbill lists the characters and usually gives some information about where and when the play takes place. As the play starts, and before any action occurs, the curtain opens showing the set and props. As a result, the audience has a complete sense of time and place before any action occurs.

To duplicate this in a trial or deposition, an attorney may have some visual options, such as diagrams or photos, and should use those if available. But an attorney must be prepared to present the stage through words the way a novelist would. And that requires getting stage setting information in discovery, particularly in deposition.

Set the Stage

An attorney should view the gathering of stage setting information as a separate and important task in taking a deposition. In Portis v. ADOT, the case used for deposition training by the National Attorney General Training and Research Institute (NAGTRI), the plaintiff, who works as a hardware store clerk. He receives a call from his child’s day camp telling him his child was injured in a fight. He immediately leaves the store, yelling an explanation to his boss as he runs out the door. On the way to pick up the child gets into a two-vehicle accident with a vehicle driven by and ADOT employee. Fault is disputed between the drivers, so one issue in the case is whether Portis exercised due care in driving to pick up his son.

At the time Portis receives the call, the layout of the store, the number of people in the store and the location of those people are all critical to building or defending an argument that his son’s injury caused Portis to be dangerously distracted, but that basic information is unknown to counsel. If Portis’ boss was the only other person in the store, would he hear the shout as Portis left the store? What if the store was crowded and noisy? The answer depends on the layout of the store and the location of Portis and the boss. If the boss and Portis were in the back taking inventory, the situation differs dramatically from Portis working alone the cash register at the front with no idea where the boss is. Depending on the answers, this information may have a bearing on whether Portis was so focused on his son’s injury that he may have failed to pay attention to other concerns, including his driving.

We’ve all heard of the journalist’s questions: Who? What? When? Where? Why? How? Instead of lumping all the journalist’s questions into a single group, we need to break them out in a way that focuses on stage setting, saving how and why for later in the deposition:

- When did you get the call about your son?

- Who was in the store at that time?

- What is the layout of the store?

- Where was each person?

Make a list, Complete the List:

- Anything else?

- Anyone else?

Before moving on to the action, the attorney must assure completeness with respect to the stage setting information. To do this, the attorney makes lists. For example, in in the deposition of Portis, the attorney will want to make a list of who was in the store when the call came in, asking “who was there at that time?”

In order to assure that the list is complete, the attorney asks the follow up question: “Anyone else?” So, after Portis says the boss was in the store, the attorney completes the list by repeatedly asking “anyone else?” until Portis says “no one else.” At that point the attorney has a complete list of people in the scene and can ask questions about each one.

This process can be repeated for other important stage setting elements. For example, if a case involves a series of meetings between the plaintiff and defendant, the attorney might ask when the two met together and then follow up with “did you have any other meetings?” An attorney should switch to questions about the action only when confident of having all relevant stage setting information.

Get a List of all the Actions

For each significant event in the case, the attorney should then make lists of things that were done or said, ensuring a complete list of actions. So, once the layout of the store is known and its established that Portis and the boss were the only people in the store, then the attorney might ask:

- What was the first thing you did or said after hanging up on the call?

- What else did you say?

- What did your boss say or do when you yelled out?

- Did your boss say anything else?

- After you yelled, what did you do?

- What else did you say or do before leaving the store?

- What else did your boss say or do?

Get the Explanation

Once the attorney gets a complete list of the actions taken during a particular event, with everything that that was done or said by every person, then the attorney should proceed to the final step of the process, which is getting the explanation.

- Why did you leave the store immediately?

- Was there any other reason you left so quickly?

- Why didn’t you walk over to your boss to ask permission to leave?

- Is there any other reason?

- How can you be sure your boss heard you as you left?

- Was there any other reason you thought your boss heard you?

The idea of creating and completing lists is also critical to witness control. By developing lists of information, an attorney can assure that the witness provides all relevant information and can choose when to return to a particular part of the story.

For example, by creating a list of people in the store, the attorney can focus on each person in an order chosen by the attorney. The attorney can explore completely the interaction of Portis and his boss without the distraction of Portis’ interaction with a customer. The attorney can return to the reaction of a customer after completing the discussion of the boss’ reaction or can deal with them all together. Either way, the choice is made by the attorney, not the witness. The information is organized in a way that allows the attorney to decide the direction of questioning.

Taken together, the concepts of setting the stage, getting the action and then getting the explanation, combined with the idea of creating and completing lists, assures that a deposition is thorough and gets all information critical to an effective story. Once that information is gathered, an attorney can create an effective set of leading questions that will confirm critical facts. That step, in turn, allows the attorney to obtain additional factual information that the witness overlooked or avoided, and sets the stage for gaining admissions.

Lead with statements, not questions

The textbook definition of a leading question is a question that suggests the answer. This definition is fine for making an objection and is important to understand when defending a witness.1 This definition does not, however, provide a good explanation of how to create a leading question that allows an attorney to control a witness. For that purpose, consider the following definition:

A leading question is not a question at all, but is a statement followed by an implied, or if necessary, spoken request for confirmation.

For example:

- You received a call about your son.

- The call came from his day camp.

There are a couple of points to think about in making a leading statement. The first is that the request for confirmation can usually be implied rather than spoken. That’s because most witnesses, when faced with a statement from an attorney, understand that their role is to confirm or deny the information in the statement; witnesses will usually not need a spoken request for confirmation. If a witness doesn’t respond to the statement, then a request for confirmation can be made verbally. After the attorney makes the request for confirmation verbally two to three times, then the request can be discontinued; at that point the witness will understand that the request is implied.

Statements have another important distinction from a question – tone. A statement is made with a flat tone. In contrast, regardless of the form of the question, the voice rises at the end of the question. The same set of words can be said in two different ways and will be perceived differently by the witness. A flat tone will invite confirmation or denial of the statement. A rising tone at the end of the statement suggests a lack of certainty that invites discussion of the point raised. If, in making a statement, an attorney uses a rising tone instead of a flat tone, the attorney will lose control of the witness.

Restate Facts in a Logical Order

After setting the stage, getting the action and getting the explanation, the next step is to confirm facts in a way that allows those facts to be used at trial for impeachment if necessary.

The first step is to determine what is a fact. The simplest answer is that in a deposition a fact is anything the witness said when answering the questions involving stage setting, action and explanation. If the witness said it, then you can assume that it is true when it is time to restate the facts.

The next step is to properly frame the request for confirmation. Again, this involves making statements and getting confirmation of those statements. The statements should involve getting one fact and only one fact confirmed. One way to think of this is to consider how people normally talk and then break that down into small parts. For example, in a normal conversation you might say to Portis:

- When you got to work you were on the cash register until you got a phone call from your son’s day camp, and as soon as you hung up you called to your boss as you left the store.

That single sentence is actually a collection of facts, each of which can be phrased as a separate statement:

- On July 24th you drove to work.

- When you got to work your boss put you on the cash register.

- You continued to work on the cash register until you got a phone call.

- The phone call came from your son’s day camp.

- When the call was over you left the cash register.

- As you left the cash register you yelled to your boss about the call.

- And right after you left the cash register you also left the store.

You should notice two things about this series of statements. First, each statement adds a single new piece of information to the narrative. Second, that piece of information is used in the next statement and is the predicate for the addition of the next fact.

Notice also that when considered as a group, this set of facts has a logical order that leads to a logical conclusion. Here, the conclusion is that Portis left in a hurry. Although this conclusion is unstated, it is there by implication.

Test Factual Theories by Expanding on the Known Facts

As you restate facts in a logical order, you can add statements that test factual theories about what happened. So, if one factual theory is that Portis was in such a hurry he left the register unattended, you would use the information above, but also add information in bold below that has not yet been confirmed by the witness.

- On July 24th you drove to work.

- When you got to work your boss was at the store.

- When you arrived, your boss put you on the cash register.

- You continued to work on the cash register until you got a phone call.

- The phone call came from your son’s camp.

- When the call was over you left the cash register.

- As you left the cash register you yelled to your boss about the call.

- You didn’t wait to hear if your boss said it was OK to leave.

- You didn’t wait until your boss took over the cash register.

- You left the cash register unattended.

- And right after you left the cash register unattended you left the store.

Here you should notice that the theory testing takes place after a series of statements that the witness is likely to agree with. An attorney is unlikely to get a witness to agree to a factual theory unless the logical conclusion of the initial restatements supports the theory. You don’t jump to conclusions, you build to them.

Get admissions by making a statement that reaches a conclusion

Very often, attorneys in deposition reach an inference and fail to confirm the accuracy of that inference. So, once you’ve confirmed information that supports a useful inference, you follow up with statements that confirm the inference. For example, one inference from the last series of statements is that Portis was in such a hurry that he caused or contributed to the accident. That inference goes to an element of the case and would available to argue in closing based on the last series of questions. However, arguing an inference is not as helpful as getting Portis to admit that the inference is correct. To force that admission, you would need Portis to confirm the following statements.

- And right after you left the cash register unattended you left the store.

- So you left the store as fast as you could.

- You did that because you were in a hurry to get to your son.

- When you left the store you got in your car.

- You got to the car as fast as you could.

- You did that because you were in a hurry to get to your son.

- You left the parking lot and got onto State Road 20.

- That took you less than a minute after getting in the car.

- You did that because you were in a hurry to get to your son.

- You were still in a hurry to get to your son four minutes later when you got to Pinetree Drive.

- And you were in a hurry to get to your son when you started your turn.

- When you started the turn the truck was moving.

- You didn’t wait until the truck came to a complete stop before you turned.

- And the reason you didn’t wait for the truck to come to a complete stop is because you were in a hurry to get to your son.

- The accident happened because you were in a hurry to get to your son.

- You were in a hurry and that caused the accident.

One thing to notice is that there is no need to rush to get to the final question. The witness must confirm a lot of statements before you get an admission going to an element of the case.

Most of the time the witness will not make an admission regarding an element of a case. An attorney should still reach for that admission because there is no downside in making the attempt at deposition. If the witness says any of these final statements are wrong, the attorney simply doesn’t make that statement in cross-examining the witness at trial. The attorney asks only those questions that got an affirmative response.

Go back to the top of the funnel

Regardless of whether the answer is “yes” or “no” to any statement, the attorney eventually returns to the top of the funnel. If the witness answers “no” to any question the next question is always the same: “Why is that wrong?” The attorney will then ask a series of open-ended questions to assure an understanding of the witness’ position on the issue at hand. This can mean going back to stage setting, action and explanation questions and making and completing lists. Once the attorney understands the reason the witness said no, the attorney goes back to leading the witness. The statements will be adjusted to account for the new information, but the goal remains the same: Restating facts, testing theories and gaining admissions.

If the witness says “yes” to all the questions relating to a particular event, then it’s time to move on to the next event. Again, the attorney goes back to the top of the funnel, asking open-ended question that set the stage, get the action and then get the explanation. The attorney then leads the witness to get confirmation of statements about facts, theories and admissions. This process is repeated until all events have been discussed to the satisfaction of the attorney. Graphically, the process looks like this:

The steps outlined in this graphic provide a comprehensive, systematic approach to gathering information on the important topics and events in a deposition. These steps provide the information needed for creating a complete story at trial or in the drafting of motions and getting information that a witness may be reluctant to provide.

- For a thorough discussion of all the different ways a question can suggests an answer, and therefore be a leading question, see Spotting a Leading Question: Not Always as Easy as It Seems, Julia Sturgill and Michael J. Dale, National Institute for Trial Advocacy Blog, Jan. 15, 2014, https://www.nita.org/blogs/spotting-a-leading-question-not-always-as-easy-as-it-seems. [↩]